Research the work of a male and a female illustrator and identify any differences pertaining to typical gender theory in art.

Historically, it has been fairly easy to identify the gender of the creator of a piece of art; there were clear 'rules' and guides which could help pinpoint who it was that made that image.

For example, male artists would tend to over-sexualise the female form, and glorify them in a beautiful and objective way. Emotions and allegories within the art would be passed over in favour of aesthetic appeal and erotic value, whereas female artists would be more sympathetic to the feelings within an image. They would also portray the female form in a much more philosophical way, often including some kind of message behind the work; along with this, the form would represent a much more 'honest' woman, raw and unpolished instead of a beautiful but flat image.

Nowadays I would say the line between an inherently 'male' or 'female' piece of work has been blurred to the extent that it's impossible to say any one artist is any one gender. Of course they have a biological gender no matter what, but the brain is much more fluid in its ideals and through the ever-changing attitudes of society and the constantly challenged 'social norm', a lot of artists mix and match qualities of both genders to help get the right message in their work.

I also think that creative thinking is encouraged more now than ever before in history. This is partly due to new technology and means of exploring and researching culture and art, and the creative industry worldwide is ever-expanding in the wake of thousands of new graduates every year, bringing fresh water to an already gargantuan ocean of creativity.

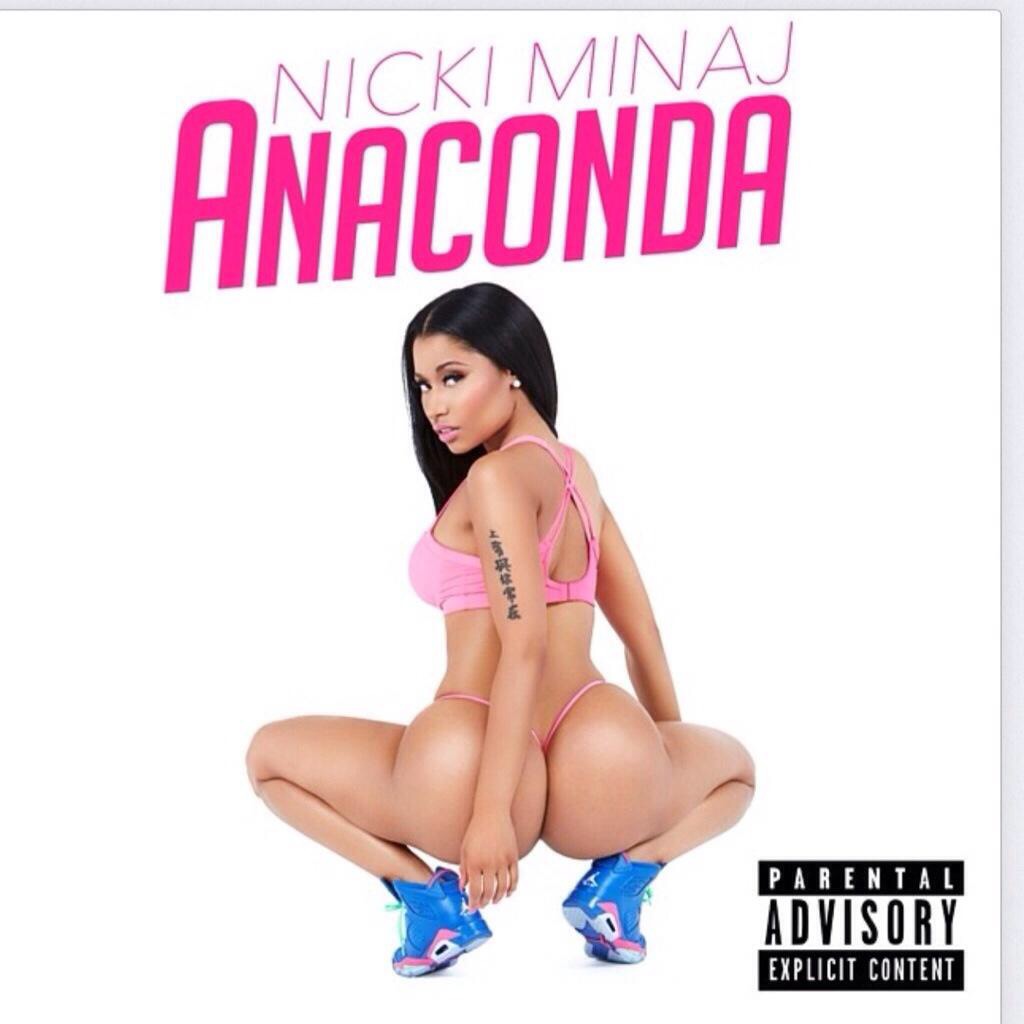

Tara McPherson

| Fig 1- Tara McPherson, Sometimes I Just Want a Hug, 2005 |

Tara McPherson is an artist in the genres of fine art and illustration, focusing on images made to exhibit, print and sell.

Typically her images feature a female model, usually in some nontypical setting or plain background. Her images do border on the erotic, often featuring nude figures, but her images try to focus on people and their relationships and provoke thought in their audience.

The aesthetic appeal of her work is strong and although the subject often possesses some macabre properties, a physical attractiveness is present also, thus contradicting traditional standards of what could be created by a female artist. Her use of colour remains sensitive and feminine though, which is what makes the combination of physical beauty and psychological reasoning work so well.

| Fig 2- Tara McPherson, Love Blows, 2005 |

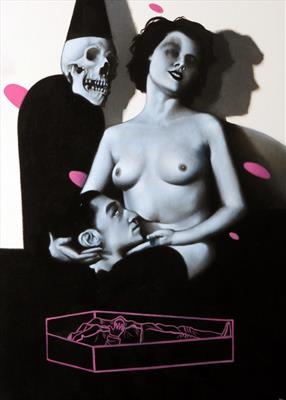

Steve Lawson

|

| Fig 3- Steve Lawson, Till Death |

Steve Lawson is another artist who crosses the lines of illustrator and fine artist. This type of mixture of genre seems to yield fantastic results of imagery combined with concept- again, although the artist is male, it challenges the common 'male' created image and shows again that in this society the lines between the genders are being less and less solidly defined.

Figure 3 shows (presumably a couple given the title) a severed male head and a woman in a sexually suggestive position and what must be 'death' standing over them. The title suggests the couple are married or bound together in some way, and the use of the colour pink helps solidify this as concept because of the way pink is usually interpreted (as a colour of love, passion and femininity/ feminine emotion).

Again, these uses of strong imagery and colour help show that the 'gender' of the creator just isn't fixed. Even in my own work I try to strike a balance between concept and execution; I want my bodies to be beautiful but I want the image itself to be an accessory to the message I am trying to make through my art.

Figure 1- Tara McPherson, Sometimes I Just Want a Hug, 2005, E. Minguet Camara, Ultimate Illustration, New York, Harper Collins, 2008, p79

Figure 2- Tara McPherson, Love Blows, 2005, E. Minguet Camara, Ultimate Illustration, New York, Harper Collins, 2008, p78-9

Figure 3- Steve Lawson, Till Death, http://www.stevelawsonart.com/index.aspx accessed 14/1/2015